FROM HIGHLANDS

TO

HOMECOMING

By Margaret P.

Acknowledgements

This story took the best part of a year to write and I could not have done it without my betas, Terri Derr and Anna Orr. Their patience and guidance were indispensable. Thank you falls short of what I would like to say to these two incredible ladies, but typically words fail me when I need them most. I will have to make do with saying that I am now very proud and pleased to call them my friends.

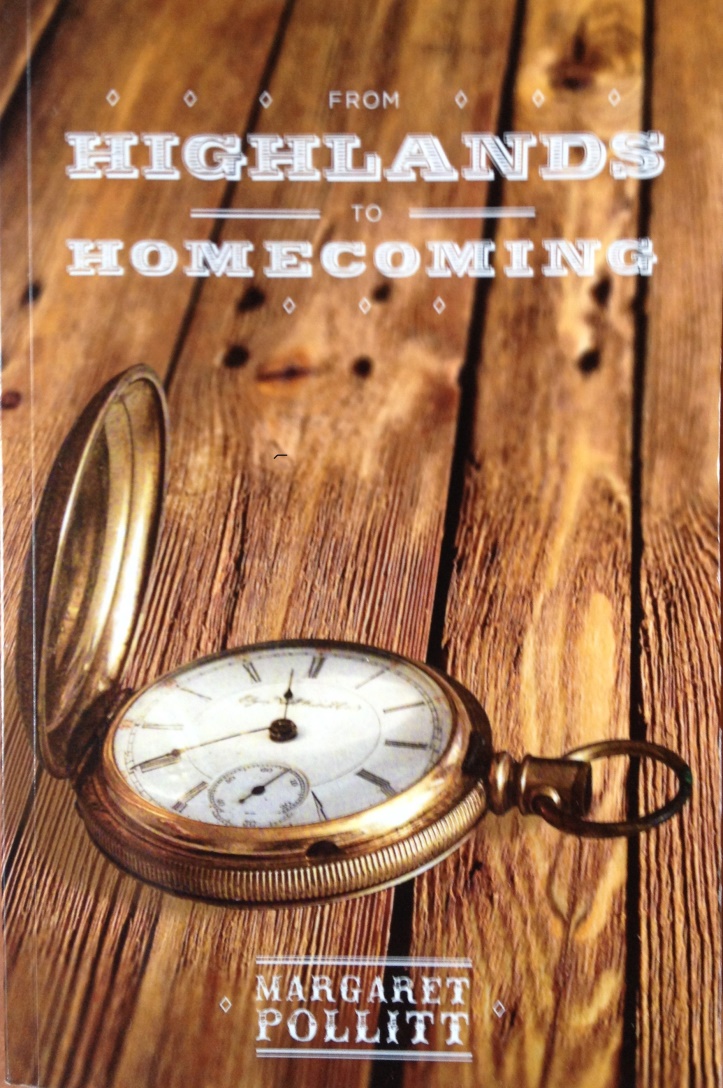

The book pictured on the title page was a gift from Terri when we met for the first time at the Spirit of the Cowboy event in McKinney, Texas in 2014. The cover was designed specifically for From Highlands to Homecoming by a very talented young graphic designer, Molly Gates.

I posted the final chapter of From Highlands to Homecoming on 13 September, 2014 from McKinney. The timing was a happy coincidence. Not only did I meet Terri and a number of other Lancer ladies connected with Lancer Writers (Yahoo) and Lancer FanFiction (Facebook), but I also had the great pleasure of meeting actor James Stacy, who portrayed Johnny Lancer (Madrid) in the television series. I owe thanks to everyone involved with the show’s creation, but in particular I owe it to the scriptwriters and to the three actors: James Stacy, Andrew Duggan and Wayne Maunder, who brought Lancer to life. Johnny Lancer has been my fantasy man since the age of twelve and Murdoch and Scott Lancer will always have a soft spot in my heart. They were my inspiration for this and other stories, and I thank them for many, many hours of enjoyment.

Contents

|

Page |

Chapter |

|

Title |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

From Highlands |

|

|

9 |

|

All at Sea |

|

|

13 |

|

Bonnie Prince Charlie |

|

|

17 |

|

In America Now |

|

|

21 |

|

The Business of Land |

|

|

27 |

|

A Series of Meetings |

|

|

35 |

|

A Novel Encounter |

|

|

39 |

|

Common Ground |

|

|

43 |

|

Boston Times |

|

|

47 |

|

Letters to Catherine |

|

|

53 |

|

Early Days |

|

|

59 |

|

The Season of Goodwill |

|

|

67 |

|

Luck Runs Out |

|

|

73 |

|

The Tide Turns |

|

|

79 |

|

The Great Escape |

|

|

83 |

|

Love and Honour |

|

|

87 |

|

Good to be Home |

|

|

93 |

|

Catherine |

|

|

101 |

|

Jud Haney |

|

|

109 |

|

God Giveth and… |

|

|

117 |

|

Grief and Anger |

|

|

123 |

|

Revival |

|

|

131 |

|

Reunion |

|

|

139 |

|

Matamoros |

|

|

145 |

|

New Beginning |

|

|

149 |

|

Discovery |

|

|

155 |

|

December 23rd |

|

|

159 |

|

Surprising Developments |

|

|

165 |

|

The Boom |

|

|

171 |

|

Ups and Downs |

|

|

181 |

|

One Down |

|

|

191 |

|

Two to Go |

|

|

199 |

|

Gone but Not Forgotten |

|

|

205 |

|

Searching |

|

|

211 |

|

Old Friends and New |

|

|

217 |

|

Women Troubles |

|

|

223 |

|

New Orleans |

|

|

231 |

|

The Chase |

|

|

237 |

|

Life Goes On |

|

|

243 |

|

Changing Times |

|

|

249 |

|

Staying Silent |

|

|

255 |

|

Abilene |

|

|

263 |

|

The Grand Finale |

|

|

267 |

|

Robbery and Reports |

|

|

275 |

|

Human and Mother Nature |

|

|

279 |

|

Loss |

|

|

287 |

|

Longwei |

|

|

293 |

|

1865 |

|

|

299 |

|

Coming of Age |

|

|

305 |

|

Worsening Times |

|

|

313 |

|

Highriders |

|

|

325 |

|

To Homecoming |

|

|

341 |

|

|

Notes |

|

354 |

|

|

Bibliography |

|

355 |

|

|

Timeline |

|

|

|

|

|

“Here laddie, take this.” Unfastening the gold fob watch the old clockmaker pressed the apprentice piece he had worn for over fifty years into his grandson’s hands. “It’s auld but it still keeps good time. It would please me to think you carried something of me in a strange land.”

Looking down, the young man accepted the treasured timepiece. “Aw Granda, are you sure? Thank you. I will think of you whenever I use it.”

The two men hugged awkwardly. Ancient hands, aged-spotted and wrinkled, then pushed his grandson towards the door. Murdoch MacKinnon, ‘Maker of Fine Clocks and Watches,’ would not see his namesake again. “Away with you. I’ve work to be doing.”

The shop bell jangled as Murdoch Lancer stepped out onto the grey cobbled street slick from the drizzle that had blanketed the town most of the morning. Funny, as much as he longed to leave, he would miss Inverness with its dour stone buildings and narrow rows of houses, its damp mists, green-black hillsides and dark mysterious waters. And oh, how he would miss that wizened, old man, who had been father and grandfather combined since his Da had fallen to his death all those years ago.

Rubbing the smooth gold between his fingers Murdoch looked up to the parting clouds, blinking rapidly, before putting the watch safely away in the top pocket of his jacket. His eyes then searched the far end of the street to find his mother and sister waiting with his trunk outside the coach house. Where was Jock?

“Behind you.” Come straight from the byre, having helped birth a new calf, Jock Lancer was still rolling down his sleeves as he strode towards his younger brother. “A bull. An easy delivery, thank God. I thought when she started, it would make me late.”

Jock threw his arm around his brother’s shoulders and they continued on together. “One down, two to go. Sure you won’t change your mind and keep working for the laird? You know he’ll have you back. Best cattle man for miles, he says—next to me of course. We share our father’s knack with them bonnie beasts, laddie.”

“No Jock, you know that wouldn’t work. The laird is changing to sheep like the rest, and besides I’ve got the hunger for adventure. It’s America for me now I’ve saved enough. It’s different for you.”

Coming to a halt, the younger man turned towards the brother he admired so much. At fourteen, Jock had taken on the roles of man of the house and bonnet laird with stolid determination, refusing Murdoch’s help beyond a few chores and insisting that he stay at school. Their Da would have wanted it that way. Supported partly by their grandfather’s generosity, Jock had barely kept the farm going that first year, but thereafter he had found his stride. He was soon teaching grown men a thing or two about raising cattle and managing a farm. As a result Glenbeath was one of the few Highland farms still able to make ends meet while continuing largely with the cattle that he and Murdoch both loved.

In his second year of farming Jock had employed another labourer to help with the heavier work. At the time his holding was not large, and he would have had to let this man go if Murdoch had come to work there. Neither he nor Murdoch wanted that, and besides Jock had better things in mind for his brother. When he had finally allowed Murdoch to abandon his books, it had been to take up a position with the local laird as assistant to the factor. Murdoch had a natural affinity with animals of any sort and coupled with the best education Jock and his grandfather could afford, the laird took little persuasion to employ him. Already knowledgeable about cattle, Murdoch would work as a stockman when needed, but would learn all aspects of estate management and eventually become an estate manager himself.

Naturally Murdoch had contributed regularly to his family’s income, but from an early age he had a dream, and he had saved most of his earnings to finance it. “I dinnae begrudge you the farm, Jock. It’s yours by right, but I want land of my own, freedom and space. Scotland can’t offer that.”

“Aye, with the clearances, folk are leaving in their droves, but there is always a place for skilled and educated men. The laird has been hard pushed to find a replacement for you as factor. He has asked Robertson to come out of retirement while he advertises further afield.”

“I didna know that, but it makes no difference.”

“No? Well, you can’t blame me for trying one last time.” Laughing with resignation, Jock gave his brother a playful shove. “Come on. Now you must pay the price for your stubbornness and bid farewell to our mother and Maggie. The coach will be for Greenock soon.”

Fresh horses were being harnessed to the mail coach by the ostler as they approached the front entrance of the inn. Smartly dressed in black and scarlet livery, the driver and guard loaded the luggage and the mail box. Jock lent a hand with Murdoch’s black leather and timber trunk, heavy with everything he was taking with him to the New World, as his brother went to bid farewell to his mother and sister.

Taking his leave of his womenfolk was tearful. Murdoch knew it would be, but there was no help for it. A youthful nonchalance and excitement to be finally on his way helped him through the worst.

Maggie tried to hide her feelings behind pragmatisms but her blue eyes watered all the same. “You’ll write at least once a month, and mind you eat properly.”

“Yes Maggie, I promise.” He smiled and nodded towards her rounded midriff. “And you look after yourself and the bairn.”

“Rob is sorry he couldn’t be here to see you off, but auld man Macpherson wouldn’t hear of him taking the time. I’m sure he’s the reason the Sassenachs say we Scots are tight-fisted.”

“No matter, Maggie. We said all there was to say last night.”

“Remember you have kin in America, but they likely spell the name differently,” his mother reminded him. “You should try to find them.”

“America is a big place, Ma, but I will let you know if our paths cross.”

Murdoch knew he was just humouring his mother. The chances of him meeting his American kin were very slim after so many years with no contact and no knowledge of where they had settled. His uncle had left Scotland well before Murdoch was born. If it helped her to believe that he would have family nearby to support him there however, he would not dampen her hope entirely, and he would look out for the name or any similar spelling.

“You’ll always be my bairn,” wept Ellen Lancer forcing her youngest to stoop to hug her for the umpteenth time. Ellen was dwarfed by her sons. In terms of height, they favoured their father, as she did hers, but courage and determination came from both parents. “You’ll be a success, son. I ken that. Oh but it’s hard to have you go so far away. You stay safe. You hear me?”

Gently Murdoch prised her arms away from his neck and kissed her tear-washed cheek as the coachman gave the final call. Turning to his brother he offered his hand. Like two towering pines, the brothers stood facing each other, drinking in the other’s image; each etching a picture in his mind that must likely last a lifetime.

“Take care of them, Jock—and yourself.”

“Good luck, brother.”

Firmly shaking hands and embracing one last time, the Lancer men parted. Murdoch hauled himself up into the carriage. The coachman cracked his whip and four strong horses headed south, hooves clattering over the cobbles and splashing through puddles. Holding back the leather curtain Murdoch leaned out waving until all sight of his loved ones was lost, and then he settled back in his seat next to a rotund scrivener. Moving his legs politely to one side to make more room for the seamstress sitting opposite, he swallowed the lump in his throat and looked to the future.

Two days later after an uneventful journey he arrived in Greenock as dusk enveloped the port. He took a room at an inn near the dockyard, so he would not have far to walk the next morning. Boarding was to be early. Ordering a good breakfast in advance, he made his way upstairs long before the singing and laughter ceased and the other patrons meandered homeward. As he drifted off to sleep on a lumpy straw mattress, images of rolling hills, wide valleys and free ranging cattle filled his mind. What would it be like to live in such a place, to own such land? If it pleased God, he would soon find out.

The distant Highlands were haloed by a rising sun as the Duchess of Argyle slipped her moorings the next morning. The breeze caught the mainsail and the emigrant ship glided towards open seas. Standing on the main deck, elbow to elbow with others making the voyage, dreams of the New World and adventure were temporarily laid aside. Picturing each loved face, one by one, Murdoch bid a silent final farewell to his family and homeland.

For the fourth time in as many minutes Murdoch heaved. Gulls circling overhead dived with great expectations but came up short as they realised that source of nourishment had dried up. There was nothing left of the good breakfast of porridge and milk followed by eggs and bacon that he had treated himself to at the tavern before boarding the Duchess of Argyle. He had felt fine as the vessel eased itself away from the wharf. Caught up in thoughts of family and home, he had barely noticed the swell increasing. When the ship reached the Tail of the Bank all the passengers had been called to the quarter deck to undergo medical inspection and to hand over their tickets, and he had happily agreed to be one of the ship’s constables. The responsibility for supervising the allocation of rations and liaising between the passengers and ship’s officers would add interest to the journey. When the barque truly broke free into open water, however, and the mainsail embraced a lively breeze, it was a different story. He began to wonder whether he would be able to stay on his feet long enough to fulfil his duties.

He was not alone. Draped over the rails nearby or collapsed in misery around the deck and below decks were many of his fellow passengers. As the ship rose and fell on the waves so did the contents of their stomachs.

“Land lubbers,” chuckled a grey-whiskered seaman behind Murdoch as he hauled on a rope to secure the rigging. Chewing tobacco he spat with precision over the side and hailed the cabin boy just about to disappear down a ladder. “Here Tom, get some fresh water for these folk.”

Water was rationed but the old sailor knew the captain made allowances for the first day or two when his passengers had particular need. The boy soon returned with a pail of fresh water and a ladle. Murdoch took a small amount to swill his mouth out and then swallowed a mouthful. His innards felt a little more settled as he nodded his thanks, and the cabin boy moved to another man further along the rail.

By late afternoon a squall got up.

“Passengers below decks,” ordered the captain as sailors ran backwards and forwards and climbed like monkeys up into the rigging to bring in the excess sails.

The single men were in the bow, about as far away from the single women in the rear of the vessel as the god-fearing owners could arrange. Murdoch was amused by a precaution so clearly unnecessary at the present moment. Male or female, many could hardly raise themselves to stand and were far from fit for anything more energetic.

Although Murdoch was no longer vomiting, others were still severely indisposed. The passengers were confined below decks in an area known as steerage, which was partitioned by heavy canvas walls with sections designated for single men, families or single women. Each section was divided by a narrow corridor between two-tier bunks with belongings and rations stacked precariously in the centre. With the slop buckets in regular use positioned at either end of each ‘cabin’, the atmosphere was highly unpleasant.

Murdoch had the extra difficulty of being taller than average. At six feet five inches he was a giant compared to most of his companions. There was little more than seven feet of head room in steerage, and it took him some time to find a position that was comfortable enough for him to fall asleep on the six foot square bunk, which he shared with three other men. In his slumber his legs sought release by extending out into the gangway. Another passenger, dashing madly in the dark for the slop bucket, tripped over them. Murdoch awoke suddenly, in time to witness the contents of the poor man’s stomach exploding forth as he hit the floor.

“I won’t get in the way, sir, but I’d be grateful if you would let me sleep on deck where there is more room,” Murdoch petitioned the captain the next morning. “I could spread out by the life boats or anywhere else you’d prefer.”

“Note in the log, Mr Adams, permission granted to Mr Lancer to sleep on deck during fine weather due to his exceptional size.” Captain Livingston’s voice was stern, but there was a glint of amusement in his eyes. “You will go below decks with the rest at other times, sir, and if you do get in the way, you will stay down there.”

“Yes sir, thank you.” Murdoch made a swift retreat before the captain could change his mind. Sleeping under stars in fresh air instead of under creaking timbers in a miasma of body odour and vomit was a concession, for which he was very grateful. He would take no risks of getting that permission revoked.

Over the following six weeks he got to know many of his fellow passengers well. He still spent about half his days and nights in steerage due to the weather conditions and routine of the ship; passengers were only allowed on deck at certain times of day when they would not get in the way of the crew. Despite the segregation of their quarters and on deck, some intermixing of the sexes still took place. As constable, Murdoch had to collect the daily rations from the galley for his part of steerage, and in doing so came in passing contact with his female counterparts. Everyone was officially allowed to mix together for church services on a Sunday, and there was the occasional dance when the weather was fine.

One day when a young shepherd was feeling unwell, Murdoch offered to feed his dogs and discovered how his bedfellow had become so friendly with a young woman from Dumfries. To get to where the dogs were kennelled, he had permission to cross over the poop deck, which was reserved for the single women. In addition, the kennels were very conveniently out of sight of the quarterdeck.

“You jammy beggar,” Murdoch ribbed the man upon his return.

“Ah well, it’s amazing how long it takes to feed three dogs,” sighed the shepherd with mock gravity as he roused himself from his sick bed to accept a smuggled gift from his Mary.

“How thoughtful,” he said, shaking out the neatly stitched handkerchief and blowing his nose vigorously. “I only sneezed a couple of times yesterday. Or do you think she objected to me using me sleeve?”

Although no particular girl caught Murdoch’s eye, with his tall good-looks he was the focus for more than his fair share of flirting. It would have been rude not to respond in kind. His mother had always taught him to be polite, had she not?

Most steerage passengers were penniless crofters evicted from their livelihoods by landlords enclosing land for sheep. Some had their passage paid for by those same landlords. It depended how you looked on it whether that was generosity or simply an attempt to assuage their consciences and get rid of a problem. The remaining passengers were those who deliberately sought greater opportunities in a new land, mainly artisans, domestic servants or skilled agricultural workers. Some a social degree higher, like Murdoch, could have afforded a cabin, but preferred to save their funds for their new lives.

When they were not allowed on deck, they were confined below in cramped conditions. Apart from carrying out basic housekeeping chores as directed by the constables, the men passed the time by playing cards or games like shove penny, carving small trinkets, talking or telling stories. Some artisans earned money during the voyage by plying their trade. Only a few like Murdoch could read and write much beyond their name. That was one reason why he had been chosen as a constable.

Many of those who were literate kept a journal, read or wrote poetry to pass the time. The ship boasted a small library for the use of its constables, and besides that the men readily shared what books they had brought with them. An avid reader with eclectic tastes, Murdoch had enjoyed Charles Dickens’ earlier works, so he had brought Nicholas Nickleby with him to help pass the time. He was not disappointed. Another passenger lent him Frankenstein in exchange when he was finished. He started to read a translation of Homer’s Iliad, but unfortunately the ship’s copy had pages missing. He put it aside in favour of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar with every intention of reading the Iliad another time when he could spare the money to buy his own copy.

Sometimes a man would read aloud, usually poetry. A book of poems by Robbie Burns naturally proved popular. Though it may not have been the best choice psychologically during a sea voyage, Murdoch’s passionate rendition of The Wreck of the Hesperus by a new American writer, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was also a favourite.

A special friendship developed between Murdoch and a young cordwainer from Hexham. Ben Telford was one of the few Englishmen aboard ship. By his way of it, he was not only escaping his father’s workshops, but also his domination. Like Murdoch, Ben was emigrating to seek his own fortune and adventure. When he was not adding to his savings by mending his fellow passengers’ boots and Murdoch had fulfilled his daily tasks as constable, they shared their enthusiasm for all they had heard and read about America. Many otherwise empty hours were filled discussing their hopes and dreams.

“I’ll get work with a Boston manufacturer for the first year, maybe two. Once I’ve earned more money, I’ll head west to a town without a bootmaker and set up my own business. I’ll prove to the old codger I can make it on my own, if it kills me.” Ben jumped his black checker piece over several of Murdoch’s red ones. If Ben thanked his father for anything, it was his insistence that the boss’s son must learn his trade like any other man before being allowed a say in how the workshops were run; the fact that his old man would not listen to any of his suggestions even when his was qualified was his main complaint. Inadvertently, however, his father had given him the key to his freedom; he had a trade as well as business experience, and he had been fairly paid for both activities while living under his father’s roof. Now he aimed to put his skills, knowledge and savings to good use in America. “I have a cousin near Boston, who will put me up for a while. That’s why I paid passage on the Duchess.”

“I’m for California eventually, but I need the help of land agents based in Boston to arrange things,” Murdoch replied. He had researched America and its neighbours for several years. Originally he had envisaged settling within the existing territories of the United States, but when he read Two Years before the Mast he knew California was where he wanted to be. It was currently part of Mexico, but from what he had read it would soon become part of the United States. It was only a matter of time. There was something exciting about being a pioneer in a new territory or state. “See here, land in the north is expected to become available soon and sell cheaply. I have a letter of introduction from my old employer to a man of influence in Boston. With luck he will be able to put me in touch with the right people. I need to borrow a little more capital to help with set up costs.”

“A little more capital? You’ll need more than a little capital to finance what you’ve written here! I know you said you’d been saving, but even in your lofty position as estate manager, you can’t have been earning that much surely? You may have to lower your sights, my friend.”

“Ah well, my brother and grandfather insisted on giving me what they said was my inheritance before I left, and it was nae just my wages that I was saving,” Murdoch admitted. “I had other income from a deal I made with the laird some years back.”

“Go on with you! The likes of us don’t make deals with lords,” Ben retorted. “Seriously?”

Murdoch shrugged and smiled. He remembered clearly the event that had proven so profitable. It could have easily gone the other way. It could have seen him dead.

Chapter 3: Bonnie Prince Charlie

“I’d been working for the local laird about a year when his prize bull calf strayed through a broken wall and fell into a ghyll,” Murdoch recalled. Moving his checker piece out of danger, he stood up from the bunk where he and Ben were playing. To relieve the cramp beginning in his legs, he reached up to touch the timbers above his head and bent at the knees up and down a few times before settling back to the game.

“A what?”

“A glen with verra steep sides.”

“You mean a ravine,” corrected Ben running his fingers back through tangled, unwashed hair. “You need to learn to speak English—well, American at any rate—if you want to do business with the moneymen of Boston. I’m told they’re a snooty lot.”

Murdoch continued unperturbed by his friend’s insult—the pot calling the kettle black after all. “The poor beast was unhurt but marooned on a ledge about half way down. The burn was deep at the bottom and there were no rocks to climb up from. It was cliff either side for several yards so there was no hope of rescue that way. The only chance was with ropes and straight down from the top.”

“And your lord ordered you down?” Ben asked incredulously. “You could have been killed.”

“Aye, I could have been. It was how my father died, trying to rescue one of his own cattle, but nay, the laird didna order me down. I volunteered.”

The memory of that day filled his mind as he retold the story. The laird had been called to assess the situation. Murdoch and three other men had stood by waiting for instruction, including the stockman whose job it had been to repair the broken wall the day before the calves were released into that paddock. Murdoch had watched the laird ride southward and look back to see what Murdoch and the others already knew.

The animal had survived the fall. It must have wandered too close to the edge where the ground had jutted out with nothing to support it. The weight had caused the soil to give way and a slide of scree could be seen to the south end of the ledge where the calf now stood. A solitary clump of gorse clung to the rocks at that point. It must have been the only thing between the calf and certain death as the rock face fell almost straight down from there to the burn below. A miracle the beast had not broken something, but it was on all fours and apart from a few scratches apparently unscathed. There was no way of reaching it however. No man could navigate the slip itself even with ropes. The cliff extended too far either side of the outcrop to make a sideways approach feasible. Straight down with ropes from the place where the men now waited for him seemed the only option, with few footholds and only a couple of hardy gorse bushes to hold onto. The last few yards to the ledge were a sheer drop and any man attempting the task would be relying solely on the rope and the strength of those at the top manning it.

Murdoch knew the laird was considering whether to send one of them down. By rights Grant, the shirker responsible for mending the wall, should be the rescuer, but he was the heaviest and he had a wife and bairns. Murdoch was the lightest and most agile despite his height, but he doubted the laird would ask him to do it. Allowing for the difference in social standing, the laird had called his father ‘friend’. He would not want to be responsible for putting Murdoch in danger of being killed in the same manner.

“Shoot it,” the laird ordered having ridden back to the waiting group. “We cannot bring the beast up safely. Better it have a quick death than starve slowly.”

Macleod, the headman, retrieved the flintlock rifle strapped to his horse. He had come prepared, guessing the laird’s decision. Valuable as the calf was, the laird held fast to the traditions of Clan Chief. To put any of his men in harm’s way for the sake of an animal would have been out of character.

“Wait.” Murdoch stepped forward and held his arm out to prevent Macleod going to the cliff edge. “Let me try to bring him up.”

“I will not ask you to risk your life to save a beast,” responded the laird.

“You’re not asking, milord, I’m offering—if the others will manage the ropes and if you will make it worth my while.”

“I’m listening.” The laird looked down at his assistant factor with interest. The bay hunter beneath him snorted and shook its head restlessly.

“If I save him, I get half the value of his off-spring.”

“Half the value of …. Ha, you’re your father’s son, all right—as canny as your brother an’ all.” The laird threw back his head and laughed out loud. “Well, if you’re sure, I have nothing to lose by the attempt.”

Murdoch grinned with youthful confidence and faced the other men. “Will you help me? Man the ropes and I’ll stand you all a drink whether I’m successful or no.”

“Aye, we’ll help,” nodded Macleod. “But leave your purse up here, laddie—just in case.”

Ropes were fetched and the three stockmen stripped off their jackets and took their positions. The laird and horse at the rear would act as final anchor as there was nothing else to do the job. Murdoch took off his coat and tied the rope securely around his waist. With smaller ropes slung over his head and shoulder he stepped back over the edge and inched his way slowly down the steep stony slope until he reached sheer drop. Finding firm footing against two lichen-covered rocks, he adjusted his grip and tested the rope once more before lowering himself over the edge as the men at the top paid out the slack to his shouted instruction. It seemed like a lifetime before his feet touched solid ground again, yet looking up there was only about thirty feet of cliff above him. The stranded calf bellowed pitifully and nudged against him almost sending him over the edge.

“Get back, you damn fool!” Shaken, Murdoch looped one of the smaller ropes around the animal’s neck and looked for something to fasten it to. Nothing—he gave up and just used the rope to hold the calf steady while he forced it down on its side and bound its legs. As the young bull struggled, however, Murdoch realised there was no way he would be able to carry the beast and climb to safety at the same time.

“You need to make a harness for the calf. Attach it to a separate rope. I think I can guide the calf over the edge, but I cannae carry it over.” Standing on the narrow ledge high above white water with hundreds of pounds of squirming, terrified beef, Murdoch cursed his own stupidity. Everything had seemed so simple when he had been safely up top. He had gotten carried away with his own cleverness for making money. He had minimised the difficulties and dangers of the task. Murdoch knew he had proved his grandda right; he was a young fool. So what that he had been correct in believing the laird’s love of ingenuity and daring would outweigh his caution, and his fondness for the late John Lancer would cause him to accept a deal more financially beneficial to his friend’s son than to himself. Murdoch should have realised from the outset that the calf would be too big and heavy to carry.

His da had descended only with ropes, but there had been a narrow path to navigate not a sheer drop. John Lancer would have succeeded except that the panicked steer had knocked him onto an outcrop, which gave way. His brother-in-law Alex Fraser and old Fergus Ross, who had manned the ropes above, had been able to slow his descent, but a minute later the steer had toppled over the edge after him. John had been crushed between the beast and the jagged rocks of the burn below. Why had Murdoch been so cocksure he could achieve such a rescue when a similar attempt by his father had gone so horribly wrong? “If I get out of here alive, Ma will kill me.”

More men were brought from a nearby field. A harness was made and lowered, and Murdoch secured it to the calf.

“Haul away!” Murdoch helped the animal avoid injury as the ropes lifted it upright. The calf rose into the air bellowing in terror. When it reached the top of the vertical rock face and could go no further without his help, Murdoch called for the men to start hauling him up. Reaching the same point he let go of the rope and grappled desperately for leverage, his legs swimming in thin air. With every muscle protesting, he dragged his body up and over the edge of the overhang onto the steeply sloping upper ground. A few minutes rest face down on the rocky incline, the plaintive sounds of the calf ringing in his ears, and then he carefully repositioned himself sideways. As the men pulled from above, he used one foot and arm to prevent himself falling and the other leg and arm to push the animal wide of the edge. On the fourth attempt he managed to manoeuvre the calf over and onto the slope beside him.

“I must be mad.” Gasping for air, he adjusted the ropes around the struggling calf. Then he cut its legs loose and helped it upright. Now the young bull could climb the remaining distance as the ropes dragged it upwards. “Stark, staring mad!”

Mad or not, Murdoch and the calf had finally reached safety and over the following years his agreement with the laird had been highly profitable. Bonnie Prince Charlie, as Murdoch christened the bull, proved no worse for wear due to his ordeal; in fact it rather seemed to have increased his appreciation of life, particularly when it came to the opposite sex. Once the animal was of age to begin breeding, his libido seemed to have no bounds and his progeny was soon to be found the length and breadth of the Highlands. Each one sold reaped Murdoch half the sale price and when he finally left the laird’s employ and the value of the stock still held was calculated, he came away with a tidy sum. Added to that was also what he and the laird agreed would be fair compensation for any future progeny. Murdoch was not prepared to relinquish his rights just because he was emigrating. He had intended to ask the laird to pay his brother instead of sending payment to America, but the laird suggested a lump sum to buy out his share. That suited them both and an agreement was soon reached.

“So how much is a cow worth and how many did Bonnie Prince Charlie sire?” enquired Ben so engrossed in the tale that he had inadvertently allowed Murdoch to nearly clear the board of his checkers.

“Enough,” replied Murdoch, “Just enough.”

Before the Duchess of Argyle docked its passengers were ready on deck with their belongings, eager to see their new homeland and to feel its solid ground beneath their feet. The ship would return to Britain within a few days, the hull filled to capacity with cargo. The crew started dismantling the bunks in steerage to allow for this even as Murdoch and Ben made their way to disembark. Behind the docks they could see the bustling city of Boston spreading out before them.

“Not as big as Glasgow, I think, but bigger than Inverness.” Murdoch gazed about with interest.

Ben stopped at the end of gangplank and grinned over his shoulder at Murdoch. “Next step American soil. Dare I do it?”

Murdoch laughed. Shoving Ben forward, he stepped onto the wharf after him; his sense of achievement exhilarating. He had made it. The first hurdle of crossing the Atlantic was behind him, and the next stage of his great adventure was about to begin.

Heaving his heavy trunk up onto his shoulder, Murdoch followed Ben through the throng of families and seamen. He was now wishing he had travelled lighter. Ben had just brought a haversack—much easier to carry on your own. The Northumbrian was no fool. The friends manoeuvred their way off the crowded pier and headed into the city as far as Dock Square.

“I’m going down Washington Street.” Ben pointed to the signpost just past a fishmonger’s stall as Murdoch lowered his trunk to the ground and rubbed his shoulder. “Are you sure you don’t want to come with me? My cousin won’t mind putting you up for a night or two.”

“That is kind of you, but I have affairs to attend to here in town. I’ll find a room near the business district so I can make an early start. I have your cousin’s address. I’ll be in touch.”

Ben was for Roxbury, a town on the outskirts of Boston. Murdoch watched him as he crossed the square. Doffing his cap in a polite negative to the invitations of a couple of early rising strumpets, who were gossiping beneath a lamppost on the corner, Ben raised an arm in final farewell to Murdoch and disappeared into the hustle and bustle of the main road going south.

Before the ladies could transfer their attentions to him, Murdoch hoisted his trunk onto his shoulder again and headed west. He wended his way through unfamiliar streets towards the business district, seeking directions along the way. Boston was much larger than Inverness. The strange sound of American accents mingled with the normal hubbub of carts and horses. He stopped occasionally just to listen and watch. There were an incredible variety of people and commercial activities, and one extremely vocal puritan on his soap box preaching hellfire and damnation. Stepping quickly back to avoid a bar brawl that spilled onto the street, Murdoch bumped into a customer exiting an apothecary’s shop. Apologising profusely he stopped mid-sentence and just gaped for several seconds—the fellow was black. Murdoch had never seen a negro before. The man was in a hurry and did not seem to notice Murdoch’s astonishment. Mercifully he was able to close his mouth and pull himself together without drawing too much attention. Still he felt incredibly foolish.

His first business was to locate the bank to deposit his gold and acquire some American currency. His laird had given him a letter of introduction to the manager of one of Boston’s leading banks. He was a relative and the laird was confident there could be none better to advise a new immigrant of means. Murdoch found the bank without mishap, a large red brick building with marble portico. Inside he was asked his business by a smartly dressed young man not much older than himself. This fellow stood near the door, and his sole purpose seemed to be to greet customers and usher them to the appropriate bank official. He escorted Murdoch to an imposing oak door and bid him wait as he knocked and went inside. Through the doorway Murdoch could see a middle-aged man in a dark suit seated behind a large mahogany desk, engrossed in the contents of a leather-bound ledger. His escort hurriedly whispered something in the other man’s ear. The manager nodded and closed the ledger. The younger man beckoned Murdoch forward as he departed.

“Mr Lancer, welcome. I am Douglas Muir.” The bank manager stood and stretched out his hand, giving Murdoch’s a hearty shake before waving him to a seat. “Young Evans tells me you wish to open an account with us and that you bring word from my cousin in Inverness.”

“That is correct, sir.” Murdoch put his trunk down on the floor and settled into one of two polished-wood chairs in front of the desk. “I’ve just arrived from Scotland and I have gold I wish to deposit for safe keeping until I can purchase land in California. I worked for your cousin for some years. He was kind enough to give me this letter of introduction.”

Douglas Muir unsealed the letter and quickly surveyed its contents. “My cousin speaks very highly of you, Mr Lancer. A man well-suited to the challenges of the west I should imagine. I’ll be pleased to help you in any way I can.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Muir referred back to the letter and then looked enquiringly up at Murdoch. “He says here you may have no small sum to deposit with us today.”

Murdoch nodded and bent to retrieve the gold from his trunk. He had stored the money bag in the strongbox in the captain’s cabin during the voyage. Since recovering it shortly before leaving the ship that morning, he had been careful not to let his trunk out of his sight.

The bank manager counted Murdoch’s worldly wealth and opened an account for his new customer without further delay, eventually dispatching the gold away in the care of a punctilious clerk with orders to return with some American currency of various denominations. While Muir talked and wrote, Murdoch noted he sounded remarkably American for a man who claimed to have only left Scotland six years earlier. “You have lost your Scottish accent, sir.”

Douglas Muir looked up from his writing, taking a moment to appraise the man in front of him. “I will speak frankly, Lancer. In America, as a rule, money speaks louder than background or name. Here in Boston, however, it’s a little different. There is an elite. The moneymen you may need to do business with take pride in being among the first Americans. They could look down on you, because of your background. Your speech draws attention to the fact that you are a new immigrant. I would suggest you do what you can to alter it.”

Recognising the bank manager was genuinely trying to help him, Murdoch was not offended. Ben had after all offered similar advice. “Useful to know, sir. I will try my best to do that.”

His business done Murdoch asked Muir where he might find comfortable, inexpensive accommodation close to the centre. He was referred to a boarding house for single gentlemen a few blocks away, owned and run by a respectable widowed lady.

Mrs Matilda Merriweather, Tilly to her friends, was a very round, very pretentious and very talkative woman of indeterminate age. Her fisherman husband had come to an untimely end when he had jumped from his fishing boat to the jetty and missed.

“Oh, it was awful. Crushed he was, crushed between the boat and the pier. My poor William never stood a chance. God rest his soul.”

Mrs Merriweather had bought her boarding house with the proceeds from the sale of her husband’s fishing boat. She only accepted men of good character into her establishment. A referral from Mr Muir at the bank was considered very satisfactory evidence of such character. The bank manager would never send her a gentleman who could not pay his way.

“A storm was coming in, you see. But they had a problem at sea and were late returning. The wind had got up. Young Obadiah was trying to secure the rope at the bow, but he saw the whole thing. Poor, dear, dear William—he tossed the mooring rope, but missed the bollard, so he tried to jump ashore. Such a brave man, but foolish, foolish thing to do in such weather. A wave took the boat up. Knocked him off balance, and he fell between the schooner and the wharf as the wave dropped.” Mrs Merriweather drew in a great breath and exhaled audibly, shaking her head and dabbing at the corner of her eyes with a lace hanky.

“It must have been very distressing for you. Did you say you had a spare room, ma’am?”

“Oh yes—the room. Please excuse me, young man. It’s the emotion of it all, you see. It still affects me. Poor widowed woman that I am.”

Murdoch endeavoured to look sympathetic, but really he was still not absolutely certain that the lady had a room available.

“There will be no spirits, smoking or women upstairs, Mr Lancer. I lock the front door at 10 o’clock. Breakfast is between 7 o’clock and 8 o’clock in the dining room, and I insist that you present yourself shaved and fully dressed. The evening meal is at 6 o’clock sharp. I don’t provide luncheon. You will do me the courtesy of informing me in the morning if you will not be in for your dinner.”

“Yes ma’am, that sounds fine. May I see the room?”

The widow led the way up two flights of stairs. “You may have one bath per week. Water is precious here in Boston, so do not waste it. We are fortunate to have our own well, but who knows how long that will last. You must carry the water up to your room yourself and empty the bath once you are done. The tin bath is kept in the cupboard under the stairs. Rent is payable weekly in advance on Fridays.”

She opened the door into a tidy but basic bedroom that overlooked the street. A multi-coloured patchwork quilt covered an iron bedstead, and a commode could be seen under one end. There was a doily-covered washstand with china jug and basin in the far corner by the casement window, and a serviceable chest of drawers with a small mirror above it to its right. The only other things in the room were an upholstered hard-backed chair next to the bed and a rather worn Persian carpet on the polished floor.

“Seeing you are such a tall young man, I’m not sure the bed will accommodate you fully, but you’ll just have to bend some. I assure you it is the standard length. You won’t find longer.” Mrs Merriweather bustled into the room and ran a finger over the dresser top. “That girl,” she huffed, taking a rag from her pocket and dusting everything within reach.

“I’ll take it,” said Murdoch. “I’ll pay up to Friday week now, shall I?” His new landlady accepted his money with a nod of approval and handed him the key before closing the door behind her. He heard her calling out for the housemaid as she descended the stairs.

Dropping his trunk Murdoch pulled his boots off and bounced up and down to test the bed springs. Folding the pillow double he leaned back on his new bed. Oh, the luxury of having it all to himself! Stretching out he found lying diagonally he could just fit within its confines. The day had been long. There was just over an hour until tea. He would rest his eyes for a few minutes before unpacking. He would just …

Sadly the good impression Murdoch had made on his landlady lasted less than two hours. He arrived late for his dinner. Mrs Merriweather made her displeasure known, much to Murdoch’s chagrin and the guarded amusement of the other guests. “You may join us for your dinner, sir—this once—but I will not stand for you to be late again. Boston is not some Highland farmyard. Timeliness is the foundation of good manners, sir, and in Boston, good manners matter. Leave your foreign ways at the door, Mr Lancer. You are in America now.”

Chapter 5: The Business of Land

Murdoch went down to breakfast in good time the following morning, eager to recover some ground with his landlady, but she was not there. He soon learned that Matilda Merriweather rarely appeared before mid-morning. Breakfast was prepared and served by the housemaid, Rose, a cheerful girl, who was a great favourite with the boarders.

“Pull up a chair—Lancer isn’t it? I’m Jim Harper, one of the longer serving inmates.” A dapper young man stood up from the table and offered his hand. “This is Charlie Beckinsale and the body behind the newspaper is Henry Thompson.” A toast-filled hand rose up from behind the Boston Post in casual greeting. “Help yourself to coffee and toast, and just let Rose know whether you want eggs and how you like them—sausage or bacon depending on the day. Today is a sausage day.”

An hour later after a well-cooked breakfast, Murdoch and Harper left the boarding house together heading in the same direction. Murdoch had an appointment with land agents in the centre of town. They were about halfway there when they stopped outside New England Enterprises.

“Wholesalers and General Importers,” Murdoch read the inscription above the entrance. “Is this where you work?”

“It is. The owner, Mr Kirby, is an excellent employer, old Boston family, very respectable. He’s grooming me to take over as manager—introducing me to all the right people. No sons you see. I, Lancer, am going places.”

Murdoch followed Harper’s directions and soon located the land agents’ office. As promised, Douglas Muir had notified G.W. Burke and Son to expect him, and he spent a very productive morning discussing potential land purchases with Mr George Washington Burke and his son, Alfred.

In addition to other types of property, ex-mission land was slowly becoming available. Vast areas held by Franciscan missions had been repossessed by the Mexican government a few years earlier and divided up into large land grants, most of which went to existing landowners. The grants were provisional for five years. Increasingly the Californio ranchos, who acquired land in this way, were legally able to sell.

“Burke and Son have been active in California for five or six years now,” explained Alfred Burke. “My father foresaw there would be an increase in the number of land transactions when the Mexican government started repossessing mission land. Once I joined the firm, I began to visit the area regularly. We have established extensive contacts and have now visited most of the estates north of Santa Barbara.”

“Some landowners with close affiliation to Spain were always likely to be unhappy under Mexican governance,” George Burke elaborated as he searched his waist coat pockets. Not finding what he wanted, the land agent paused and went over to the coat stand near the door. With a grunt of satisfaction, he retrieved a vesta case and tobacco pouch from the side pocket of his jacket and began to fill his pipe. “Many landowners of pure Spanish blood think too highly of themselves and resent being told what to do by Mexican riff-raff.”

“Father, watch where you throw your matches. You’ll start a fire.” Mr Burke Junior hastily picked up a blackened match from some browning parchment and transferred it to the ash tray on the mantelpiece. “It stands to reason too that more and more of those who acquired grant land early will want to sell now their ownership is confirmed.”

“For the past two years we have paid a resident surveyor a stipend to relay information back to us. He acts as our agent. More and more Californios are approaching us to sell land on their behalf. We currently have two substantial tracts on our books that might suit. The Estancia Diaz is here on the coast some distance north of the San Francisco Bay.” Mr Burke Senior pointed to a large map on the office wall. “It’s about the size you had in mind.”

“No, Father, that land is more suited to horticultural use. Mr Lancer is a cattleman. Now the San Joaquin estate on the other hand would be perfect.” Unrolling a large map, the younger Mr Burke pointed out both estates, but his enthusiasm for the land in the San Joaquin Valley was clear. “We have only just been contracted to sell the Estancia Talavera, and it is an excellent property. It will not last long on our books, even though it has been neglected by its owner for the past year. The estate comes with established cattle herds and a workforce. More land will become available, Mr Lancer, but I visited this estancia two years ago before Señor Talavera returned to Spain, and frankly I do not believe you could do better.”

Unfurling another large chart, Alfred Burke showed Murdoch a more detailed view of the ranch’s boundaries while his father enjoyed his pipe and went to the window to investigate the source of a commotion outside. “As you can see, it is more centrally located than the other estate, with a variety of land, but mostly suitable for cattle. It’s within two days ride of Yerba Buena where ships regularly stop for hides and tallow.”

“Get that muck out of here!” The immaculate Mr Burke Senior hollered like navvy through the open sash. Murdoch and Alfred Burke moved quickly to the other window to see what was happening. A pure-finder’s barrow had been clipped and overturned by a brewery dray as they passed each other. Now the contents of the barrow were spread over the street outside the land agents’ office, and the pungent aroma of dog faeces was beginning to fill the air. The pure-finder was screaming insults at the drayman, whose Anglo-Saxon response was clearly heard by all three men. George Burke slammed the window shut and straightened his vest. “Now where were we?”

Grinning at the gentleman’s sudden change in demeanour, Murdoch went back to the desk and turned his attention once again to the maps. He recognised the potential of the property immediately. He had researched California as far as possible before leaving Scotland. He knew this area had land suited to cattle, but he also knew water was a fundamental consideration. The map in front of him showed a significant river as well as a small lake and some smaller streams. Upon request, Mr Burke provided more maps, geographic reports, sketches and a written description of the land; its climate and population; and what towns, resources and transport links were nearby.

The land comprised secularised mission land and other land adjoining. By the terms of the original grant the mission land could not be rented or subdivided and no public roads could be closed. The profits from hides and tallow were modest, and the Mexican government currently restricted trade through high customs duties. These considerations limited the value of land, but Murdoch was still surprised the asking price per acre was so low.

“This is not Scotland, Mr Lancer. There are very few people and even fewer, who know how to develop the land or who have the inclination to do so. You have read Two Years Before the Mast? Yes, I thought so. Dana does not exaggerate. Many existing landowners are not driven to enterprise.”

Mr Burke Senior sat down at his desk and surveyed Murdoch through pince-nez spectacles. “We have been contracted to sell this land, and we have encouraged the owner to offer it at a very reasonable price as he wishes to liquidate his investment quickly in one transaction. We do not wish to waste your time or ours by misleading you. The price per acre reflects the emptiness of the country, the current income and legal limitations, and the vendor’s eagerness to sell. It also reflects the undeveloped and variable nature of the land. Within this parcel there are some very fertile areas, some excellent pasture, a little cultivated land and much more yet to be developed. Horses roam wild and are free for the taking. There is, however, also some rough hill country and barren wasteland. Some of these more difficult areas could be brought to life with investment and hard work, but other parts are unlikely to ever be productive for agricultural use. Cattle are raised on the estate for a modest profit and have been for several years. We believe there is potential for higher profits through cattle and other enterprises, but there is no denying that it will take foresight and a lot of effort.”

Murdoch knew he would be buying potential income after a lot of hard work rather than immediate comfort. He would be gambling on a growing population and increasing demand for cattle products over time. Like the Burkes, he believed strongly that the expansion west of the United States, new technology like railways and steamships and possibly even new trade between Pacific nations would increase the market for beef and other cattle products. His research had told him that land prices were low. He had expected to buy more land than was common in Scotland, and he knew that was needed to make a Californian ranch viable. He had not expected an estate of this size however, and he was somewhat daunted by the prospect. There were no land taxes under the Mexican regime though, and in every respect other than size the estate was exactly what he was looking for. Unbelievably the asking price for the estate in its entirety, including cattle and chattels, fell just within the bounds of what Douglas Muir had indicated the bank would lend based on the deposit he proposed, the money he would have left and the knowledge, expertise and reputation he brought to the enterprise.

Murdoch’s gut told him this was an opportunity too good to pass up. Only viewing the property would confirm his choice, but he was optimistic. “Sirs, I can hardly believe I am saying this, having only just arrived in America, but I am very interested.”

“Excellent! The land grant was provisional on certain conditions. We have confirmed that all were met by the current owner, at least to minimum standards. To be secure of your purchase, we would recommend you do more comprehensive surveying and marking, and that you endeavour to meet every other condition as well.” Mr Burke Senior peered over his long nose and spectacles, making sure he had Murdoch’s full attention. “It is important that you abide by the rules, Mr Lancer. You must leave no doubt to your legal title. We have it on good authority that land title would be rigorously scrutinised if California became part of America. You would be safeguarding your interests under both governments if you were meticulous in this respect.”

“Understood. Is there anything else I should know?”

“You must apply for Mexican citizenship as soon as you commit to the purchase,” Alfred Burke advised. “The original grants were only made to Mexican citizens and California is still part of Mexico.”

“Are you a religious man, Mr Lancer?” enquired Mr Burke Senior.

“I believe in God, if that is what you mean? But wait, I know what you are going to say: to be a Mexican citizen one must be Catholic. I am.”

“You surprise me. I somehow thought you would be Church of Scotland.”

“I’m both,” replied Murdoch, enjoying the puzzled looks. “My father’s family is still papist. It’s not uncommon in the Highlands, though increasingly the Kirk is taking over. My mother’s family is Protestant. I was brought up in that Church, but my father never converted. His sister persuaded him to have all his children baptised when I was just a babe—done in secret, behind my mother’s back. There was hell to pay when she found out. The two women haven’t spoken since, though I understand they had plenty to say to each other at the time.” Murdoch chuckled.

“Fiery?”

“That would be putting it mildly—or so my brother told me. Neither woman is known to back down from an argument, and while I’ve only seen my mother really angry once, I can tell you the sparks fairly flew.”

“I take it you were the target of her displeasure?”

“Aye, a small matter of a calf and a ravine. Perhaps I’ll tell you about it one day, but after that my sympathies lay squarely with my Auntie Morag. Besides, unwittingly she did me a great service. I have a parchment that confirms the baptism amongst my papers.”

“Well, it certainly makes things easier in the first instance. We predict California will eventually transfer to American control, and then it will likely not matter.” Mr Burke Senior started to rummage around his desk. Stacks of files teetered along one edge and scrolled maps of varying sizes were scattered among a jumble of other documents. Murdoch had never seen such apparent disorganisation. It was in stark contrast to the son’s orderly desk, upon which they now worked. “Where have you put my pipe, Alfred?”

Ignoring his father, Alfred Burke continued, “If and when California does join the Union, we recommend you apply for American naturalisation promptly. It would be an advantage to be an American citizen when confirming your claim to the land under the United States government.”

“I’ve always hoped to become American eventually.”

“A clipper, the Mary Ann, is scheduled to leave for South America in just under four weeks. I have already booked passage to Chagres for my own purposes. The river and mule journey across the Isthmus of Panama and then on by ship is by far the fastest way to get to California. We would disembark at Monterey, the centre of government and about three days ride from the Estancia Talavera. If you wish to proceed, I will arrange for you to accompany me.”

Finally finding his pipe where he had left it on the window sill, Mr Burke Senior reminded Murdoch he would need more than just the purchase price. “You need to cover set up costs and have access to enough capital to cover your expenses until your ranch begins to make money. The hide market in particular is profitable and several Boston businesses are involved so you should not have too much difficulty in finding a backer with your credentials, though it will depend on what you are prepared to put up as collateral. I doubt the bank will lend beyond the mortgage on the land until you demonstrate your ability to make a go of it.”

“Aye, Mr Muir, the bank manager, has already warned me that would be the case and has given me the names of some potential investors,” Murdoch agreed, pulling a list from his pocket. “I had not envisaged finding suitable land so soon, but now that I know what it will cost me and have evidence to support my application, I’ll visit these gentlemen and see what can be arranged.”

“Who has he suggested?”

“Edgar Harraway, George Muller—and Harlan Garret as a last resort, though he didn’t say why. Do you know anything of them?”

“All are men able and willing to invest in more risky ventures for a decent return. I would avoid doing business with Garrett if you can, but it will not hurt to sound him out. The knowledge that you are talking with him might stir one of the others to support you. There is a degree of competition between such men.”

“And why should I be wary of Mr Garrett?”

“On your voyage from Scotland, sir, did you happen to see any sharks?” replied Mr Burke Senior, blowing a large smoke ring into the air and watching its progress before looking enquiringly at Murdoch.

“No, sir, but I hear they are most unpleasant beasts.”

“Once a shark bites, Mr Lancer, it does not let go. Its jaws are made that way. Once Harlan Garrett invests money in an enterprise, he has a tendency to behave in a similar manner. His contracts have been known to make grown men cry when they realise there is no getting rid of his interest in their businesses. If you are forced to deal with Harlan Garrett, Mr Lancer, make very sure you employ a good lawyer and read the fine print before you sign.”

Chapter 6: A Series of Meetings

Murdoch had every intention of employing a good lawyer regardless of any dealings he may have with the infamous Mr Garrett. Douglas Muir had set up an appointment for him with a personal friend, James McIntyre, who had offices conveniently situated between the bank and the land agents. After another meeting with Muir the next morning, Murdoch headed to the lawyer’s office eager to make his acquaintance and to familiarise him with his plans.

As he approached McIntyre and Associates he saw two young women leave the building. They were clearly friends as they were chatting and laughing and paying too little attention to the steps they were descending. The more animated of the two stumbled, and Murdoch ran forward to prevent her falling to the pavement.

“Are you all right, Miss? He supported her as she hopped back to sit down upon a lower step.

“Oh yes, thank you. Silly of me, I should have been looking where I was going.”

“You’ve hurt yourself, Catherine. I’ll get help from inside.” Her friend made to go back up the steps.

“Don’t fuss, Beth. You’re acting like father. I’m not a porcelain doll. I’ve just twisted my ankle a little. It will be fine in a moment.” Raising her skirt slightly the injured girl rubbed her ankle and Murdoch enjoyed a quick glimpse of her neatly booted foot and white stocking before he remembered his manners and looked away.

“I am obliged to you, Mr…?” She raised grey-blue eyes to take in her gallant rescuer properly. Murdoch turned back to face her.

“Lancer, Miss—Murdoch Lancer.”

“I cannot thank you enough for your quick thinking, Mr Lancer.” She smiled shyly and blushed. “I believe with your assistance, I could stand now.” Murdoch was entranced. Ash-blond ringlets framed the young woman’s face and the soft blueness gazing up from behind long ashes was mesmerising. She stretched out an elegant, well-manicure hand, and he helped her to her feet. Still holding on to his arm, she tentatively put weight on her injured ankle. “You see—good as gold.”

“In that case, we should be going,” declared the other young woman, checking the small watch on her chatelaine. “You must excuse us, Mr Lancer, but we are late for an engagement.”

The two friends hurried away, arm in arm. Murdoch watched their progress down the street, their heads together in deep discussion. Reaching the corner, they looked back, but seeing his eyes still upon them, they turned quickly away. A moment later they were gone.

His thoughts were still on Catherine with the grey-blue eyes as he entered the lawyer’s office.

“May I help you, sir?”

Murdoch stated his business and was invited to take a seat opposite the secretary’s desk. “Mr McIntyre is finishing preparations for his court case this afternoon. He won’t be long.”

Picking up a copy of The Liberator from the pile of newspapers and magazines next to him, Murdoch scanned the first article before pretending casual conversation. “I passed two young ladies as I came in. They seemed in a great hurry.”

“Miss McIntyre and her friend, do you mean?” The secretary dipped his pen into an ink pot and continued to transcribe the many-page document on his desk. From Murdoch’s vantage point, it looked like some kind of contract.

“I suppose I do,” answered Murdoch, casually crossing his legs. “Is Miss McIntyre called Catherine?”

“No, no, that is her friend, Miss Garrett. Miss McIntyre is Elizabeth, the darker of the two.” Pausing, the man looked over at Murdoch, taking him in properly for the first time. “Why do you ask?”

“Oh, no reason. Well, actually that isn’t true. Miss Garrett took a fall on the front steps, and I was thinking I should make inquiries later to be sure she is all right.” Murdoch folded the newspaper and glanced up at the secretary. “You don’t by chance know her address?”

A small bell tinkled in the background.

The older man’s eyes twinkled. Murdoch tried to hide his embarrassment; his attempt to maintain an air of innocent enquiry had failed miserably. The secretary got to his feet. “She is not a client, but I know her father’s name and I have an idea where she resides. I can look the address up for you in the directory while you are talking to Mr McIntyre. He is ready for you now. This way.”

His meeting with the lawyer took little more than half an hour. James McIntyre seemed an efficient and intelligent gentleman. He promised to get the legal documents from Burke and Son, and review them thoroughly.

“I have dealt with George and Alfred Burke before and don’t foresee any difficulty. Theirs is an established and reputable firm. It’s always wise to examine sale and purchase agreements with a fine-toothed comb though, especially when foreign laws are involved. One of my associates specialises in Mexican law so I will get him to examine the documents as well.”

Murdoch commended the lawyer for his thoroughness and then broached the subject of his potential backers. McIntyre did not represent any of the three men recommended by Douglas Muir.

"Conflict of interest. Besides there’s too much profit to be made in arguing against them and dissecting their contracts.” The attorney smiled as he rose from his chair to escort Murdoch out. “Joke, Mr Lancer. I’m joking.”

Murdoch laughed along with him but suspected McIntyre was only half joking. Nevertheless, Murdoch left the office of James McIntyre and Associates in good humour; he had Catherine Garrett’s address tucked safely away in his coat pocket.

He had not gone far when he bumped into Jim Harper. “Hold up, Lancer and I’ll introduce you to the gastronomic delights of Boston’s eating houses. I’m on my way to lunch. Just dropping these papers into our lawyers first.”

“Your company uses McIntyre and Associates? I’ve just hired Mr McIntyre as my legal adviser. He came highly recommended by my bank manager.”

“Yes, very efficient and reliable. New England Enterprises has used James McIntyre for several years, and he has built up a good team of associates. McIntyre is an abolitionist of course, so some don’t like him, but I can assure you he is not a fanatic, and he is very good at the law.” Jim hurried off and true to his word was back within a few minutes.

He took Murdoch to the Oyster House in Union Street. Seated around the semi-circular bar, they tucked into generous bowls of clam chowder and fresh baked bread. Not satisfied, Jim then ordered a dozen oysters to share.

“My treat,” he declared toasting Murdoch’s beer with his brandy and water.

Murdoch accompanied Jim as far as his office and then headed off to locate and make appointments with the three potential investors. Their businesses were all in the same general area, and it did not take him long. After that he went to collect the letters of introduction promised by the bank and the portfolios of documents from the land agents that were to be ready for him by 4 o’clock. He now had everything he needed to make his case for backing, and little more than three weeks to wait before sailing to California.

XXLXXAXXNXXCXXEXXRXX

His first appointment was the following morning with George Muller at 10 o’clock. An outwardly amiable gentleman, George Muller had the unnerving ability to make men divulge more than they intended.

“Welcome, Lancer. Take a seat.” Accepting the papers Murdoch offered him, Muller tossed them unceremoniously onto his desk. Pouring two large glasses of brandy from a crystal decanter on the side cabinet, he handed one to Murdoch with a friendly smile. “Imported from France—the only vice I admit to.” Muller winked and swirled his brandy around the glass a few times before quaffing a healthy mouthful. With eyes closed, he savoured the flavour and then addressed Murdoch with mock consternation. “Drink up, young man. First class Cognac is for drinking not looking at.”

Returning to his desk he read quickly through Muir’s letter of introduction and skimmed the contents of the land agents’ portfolio. “Tell me about yourself.”

“What would you like to know, sir?”

“Everything. Start with your successes and your plans for California. What challenges do you expect to face there?”

Murdoch outlined his background and his plans for the future with enthusiasm. Muller spoke very little, preferring to let Murdoch fill any silences that arose. Every so often the businessman would egg Murdoch along by praising him for a decision or course of action taken, congratulating him on the gambles that came off. Murdoch relaxed into friendly conversation and shared stories that he never imagined would form part of this meeting, including the tale of Bonnie Prince Charlie.

The bank was prepared to lend Murdoch a substantial amount of money, and Muller made no secret of the fact that he was impressed. “I knew if that wily old Scot was willing to part with his bank’s money to a man of your age, there must be something to you.” He topped Murdoch’s glass up and settled back into his chair. “No doubt made a few mistakes as well though, eh Lancer? Lord knows I’ve made plenty. Tell me about some of them—always good for a laugh in hindsight, don’t you think? What have you learned?”

The topic was introduced so casually, with such bonhomie, that Murdoch very nearly disclosed one of his more serious gaffes. Just at the point when he felt the urge to let words run away with him however, a crucial piece of brotherly advice sprang to mind. Jock had always warned him never to say more than was necessary when negotiating. Information was power. “Keep as much power as you can in your own hands. The principle holds true whether you are negotiating a loan or buying a heifer.”

Aware that he may have already said more than was wise, Murdoch reined in his words. This time he answered more cautiously with the hope of making light of youthful acts. He now realised some could be seen in an adverse light by a potential investor. “I believe my adventure with the calf was my most impetuous act, Mr Muller, and that was a calculated risk. I wouldn’t have attempted it if I hadn’t known the men well and trusted them. I was in no real danger with them supporting me, and fortunately my exploits paid off. Even so, I believe I have matured from that time. Business will always involve certain risks, but I intend to take a little more care of my life and your investment in future.”

George Muller continued to encourage Murdoch to talk, never asking any question that could be answered simply yes or no, and always appearing to be in sympathy with Murdoch’s actions and decisions. He flattered and laughed, but Murdoch stopped drinking his brandy and took more care with his answers. Upon reflection he had revealed a lot more about himself and his plans than he had intended, but he would not make it any worse. The gregarious Mr Muller eventually gave up his delving. Murdoch departed unsure whether the meeting had been a success or not.

Harraway was easier to deal with. Again he took little notice of the paperwork, saying he would read it later. He said he wanted to find out about Murdoch the man, but in fact, during the first half hour, he talked much more about himself. “Harvard educated, Mr Lancer. Studied the law but went directly into the family business. The Harraways came out on the Mayflower you know. Now not even my good friend Sam Cabot can claim that!”

Edgar Harraway was a frightful snob. Recognising this, Murdoch made a real effort to tone down his Scottish brogue. It pricked his conscience a little, but he exaggerated his brother’s wealth and the closeness of his relationship with his former employer. Without actually lying, he allowed Harraway to believe that the money he had in the bank was a truer reflection of his background than it actually was.

“So you are related to the Earl?”

“Yes sir. My father and the Earl were cousins. They hunted together in their youth and remained good friends until my father’s death. The Earl has always taken an interest in my affairs.”

It was all true up to a point. There are cousins and there are cousins; the kinship was very distant. Similarly, ‘friends’ may have been too strong a word to describe men, who as adults moved within different levels of society. Certainly, the laird had always taken a pleasing interest in Murdoch, but how much that was due to the deal they had struck and the fact that he worked for the man, Murdoch was not entirely sure himself. All things being equal, however, Murdoch departed reasonably confident of Edgar Harraway’s interest.

That left Harlan Garrett. Murdoch approached this meeting the following day with more trepidation—the disadvantage of listening to others. The plushness of the businessman’s premises did nothing to put him at ease. Thick Persian carpets lay over highly polished floors. Leather upholstered furniture and the very best mahogany and inlaid desks and cabinetry combined to make the office almost as daunting as the man himself. The other two men had not displayed their wealth at their place of work so blatantly, unless he counted the brandy.

Harlan Garrett was clearly well-to-do and not embarrassed to show it. A greying man around fifty of average height richly dressed and well-groomed, he was not handsome but exuded that aura of power and influence that cannot help but intimidate and attract. Social standing was obviously important to him, and Murdoch’s youth and newness to America were immediately commented on with disdain.

“Why should I risk my money or reputation backing a young man who only just stepped off an immigrant ship?”

“Why do you ever risk investment, sir? The rate of return on your investment is negotiable. With the help of Mr Muir from the bank, I have prepared a proposal that I believe is fair to both parties, but nothing is set in stone.” Murdoch looked Garrett directly in the eye. He needed a backer, but he did not want Garrett to get the idea he could be easily intimidated.

The businessman leaned back in his chair and was silent for several minutes. Murdoch felt uncomfortable under his gaze, and was almost relieved when the interrogation began. What were his plans and what evidence could he provide to prove his ability to fulfil them? No pretence of affability in this interview. Murdoch felt like he was being appraised like a diamond in the rough. Was the gem worth the polishing or would cracks appear? What would its ultimate value be and can I own it? No, Mr Garrett, you cannot.

“The particulars about the land are here, sir. With the bank’s help, I can finance the purchase myself, but that will leave me with less capital for initial running costs than I should wish. The bank will not lend to me in my own right for that purpose until I have established a credit history in this country. What I am looking for is an investor to guarantee me a line of credit either directly or through the bank for up to five years.”

“By which time, if successful, the bank will lend to you in the normal way, but in the mean time you are a risk.” Garrett wrote a calculation on the blotter in front of him, contemplated the numbers for a moment and then crossed them out. “What you propose is a very great risk. California is a long way off and currently part Mexico. While there is some talk of it eventually coming under American control, that is not likely for several years. All manner of catastrophes could befall you or your enterprise. I know nothing of you as a man, or, perhaps more importantly, as a cattleman and businessman, than what is contained in these letters and what you tell me of yourself. You are very young and you have no social or financial connections of any worth in this country. I am thinking, if I make you an offer of investment, it would require more substantial collateral than you have indicated here.”